A large jacquard tapestry, a video installation and a book published by Marsilio Arte: these are the “chapters” of “La desinenza estinta”, Lucia Veronesi’s project winner of the twelfth edition (2023) of Italian Council, the programme that promotes Italian contemporary art in the world. It is included in the civic collections of Ca’ Pesaro in Venice and is narrated by the artist herself in the pages of the book she edited together with Paolo Mele and Claudio Zecchi. Here is an excerpt

La desinenza estinta (“The Extinct Desinence”) is an artistic project on cultural cancellation that develops on three levels.

The first is inspired by a study of indigenous languages and the loss of medicinal knowledge, conducted by Rodrigo Cámara-Leret and Jordi Bascompte of the University of Zurich.1 Their research covered three macro-areas: North America, Northwest Amazon and New Guinea. The indigenous peoples of these areas hand down their knowledge of the uses of medicinal plants only by word of mouth. Many plants and their pharmaceutical uses are known only in certain languages. If those languages become extinct, their knowledge also disappears, and so do the plants. They will continue to exist on Earth but no one will be able to recognise, name and use them any longer. It is estimated that 30 percent of all languages will be extinct by the end of the 21st century. The medicinal knowledge of indigenous cultures is seriously threatened.

The plants considered by La desinenza estinta come from the Northwest Amazon. Here we record their indigenous names and their respective languages, geographical area, degree of extinction of each language, scientific names of the plants and their medicinal uses.

For indigenous plant names, their medicinal uses and the names of the peoples, reference was made to The Healing Forest: Medicinal and Toxic Plants of the Northwest Amazonia, by Richard Evans Schultes and Robert F. Raffauf. Their scientific names, the names of the languages and their degrees of extinction are derived from the research by Cámara-Leret and Bascompte. To assess the degree of threat to the languages, the two scholars consulted Glottolog as their main source. This derives the AES (Agglomerated Endangerment Status) from the databases of the UNESCO Atlas of the World’s Languages in Danger, and Ethnologue: Languages of the World by SIL International (Summer Institute of Linguistics). This first level inspired the images of the botanical collages, with brief captions.

The second level of loss concerns women who worked in botany from the 18th century to the 20th. They were female scientists and illustrators who, in their homelands or in distant countries, collected specimens of unknown plants and classified, catalogued, studied, drew and painted them. Many of them have been cancelled from the history books, or had to struggle hard to gain professional or academic standing. These are stories of women who, although differing in their training and social backgrounds, worked unpaid for years, won recognition late, disguised themselves as men to take part in scientific expeditions, or were excluded from botanical missions because they were considered unsuitable as women.

One example of the many possible is Katharine Dooris Sharp. Born in Ireland in 1846, she moved to Ohio in the United States. Without a scientific background, she was a writer and an active suffragette, and made a substantial but underappreciated contribution to botany. She contributed 447 species collected and catalogued to the Ohio State Herbarium. She travelled widely in the United States and Europe, contributing to various magazines, and published articles supporting women’s right to vote. In 1913 she published Summer in a Bog, an account of her work in a remote Massachusetts wetland. She wrote: “But while the road to scientific attainment is for the man broad and well-paved through centuries of use, there is generally for woman, when she dares to walk therein, a look askance and a cold reception.”

Most of the women botanists mentioned here, and evoked by the collages, had one or more plant species named after them, often derived from their married surname. For this reason, their maiden names also appear in these pages.

The relation between the first two levels of La desinenza estinta resemble a mathematical proportion: languages are to plants as the names of botany are to the history of science.

La desinenza estinta is given its formal synthesis in the creation of a stop-motion video and a large tapestry woven on a Jacquard loom.

The third level of the project is thus ideally connected to the fruitful example of Hannah Ryggen, one of the most important Norwegian artists of the 20th century, whose tapestries combined political motivations with formal patterns. Ryggen raised the technique of weaving to the most refined levels of contemporary art. She was also an activist who often used art to denounce social and political injustices. Her works, entirely hand-made on a vertical loom, are like huge posters, where abstraction and figuration construct a complex narrative, on the cutting edge of the most advanced artistic research of her time. In her tapestries, the textile element itself is an ingredient taken from the Norwegian landscape, which thus entered her work concretely, intensifying the relationship of images with nature. Her work can be read as an eco-philosophical reflection: the relationship between human beings and the natural environment involves both the subjects represented and the organic matter of which the tapestries are made, as well as the conditions in which they were made.

Finally, this publication does not aim to fill a scientific or cultural vacuum of centuries of history. Rather it serves as a tool of visual research, and complements the work done in tapestry and video. These three objects dialogue with and complement each other.

The publication, in particular, records on the whole the annual path of research conducted between London, Zurich and Trondheim, without retracing the stages in a chronological sequence. Each aspect recorded in these three phases is a thread entwined with a broader and more complex story; a story that is both local and universal, whose formal outcomes, including collages of plants and botanists, videos and fabrics, open up new visual paradigms, new figural and chromatic compositions.

Lucia Veronesi

The text is taken from the book Lucia Veronesi. La desinenza estinta, Marsilio Arte, Venice 2024.

BIO

Lucia Veronesi is a visual artist. Her most recent exhibitions include: Da sola nel bosco, Venice, È successo il mare, Polignano a Mare, A Bartleby, Venice.

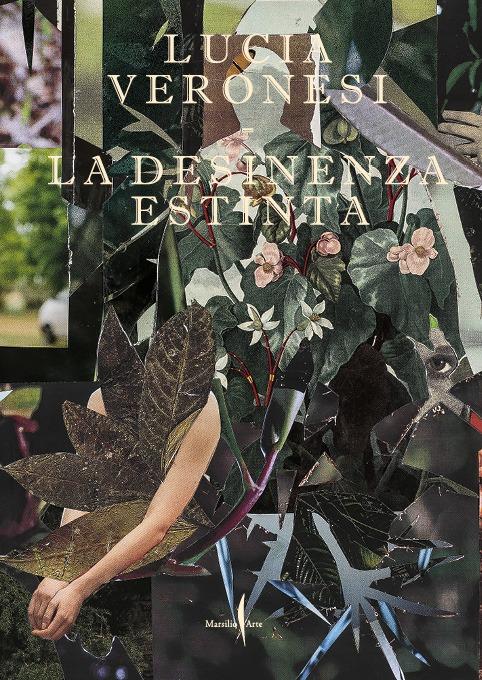

Cover photo: Lucia Veronesi, La desinenza estinta, 2023. Jacquard fabric with lampasso effect of wefts, 300 x 500 cm. Ca’ Pesaro ‒ Galleria Internazionale d’Arte Moderna, acquisition thanks to the XII Italian Council, the programme for the promotion of Italian contemporary art in the world of the Directorate-General for Contemporary Creativity of the Italian Ministry of Culture

Related products

Related Articles