The historian Annie Cohen-Solal wanted to re-examine this “great love” France had for Pablo Picasso by thoroughly scrutinizing the archival documents and arrived at unexpected and in some respects disconcerting conclusions. Contrary to what is commonly believed, France repeatedly demonstrated sincere and open hostility towards this “Spanish” artist, defined as a “foreigner”, “anarchist” and, moreover, an exponent of an “incomprehensible art”.

In 1901 Pablo Ruiz Picasso ‒ who had chosen to reside in the French capital ‒ found himself immediately investigated by the Parisian police, who opened a file on him eloquently entitled: “Foreigner n° 74,664”.

The file would be updated periodically for many years, not just with the conspicuous SPANISH stamp (in capital letters) often placed on the papers, but also with judgments that denoted political distrust towards him, contempt for his art and even tones of actual xenophobia: “He did not serve in the military in our country during the conflict in 1914”, he is a “self-styled modern painter”, he “is a Soviet apologist”, he is an “anarchist monitored by the prefecture” and then “he speaks French very badly, as he can barely make himself understood”.

Despite these hostilities, the “foreigner” Picasso was producing masterpieces in France. In Paris he had painted Les Demoiselles d’Avignon (1907). In 1929 he had offered it as a gift to the Louvre, but the museum disdainfully refused. Then came Guernica (1937), which the artist painted overwhelmed by the horror of the Spanish civil war in a France, however, completely indifferent to that fratricidal tragedy, a precursor to the massacre of the world war.

In 1940 Picasso attempted to become a naturalized French citizen, but his aspiration was crushed. This was the reason given: “Foreigner without qualifications to obtain naturalization; however, given the foregoing, he must be considered extremely suspicious”.

Worse happened, in 1942. To renew his French residency permit he was forced to declare: “I, the undersigned, declare on my honour that I am not Jewish”.

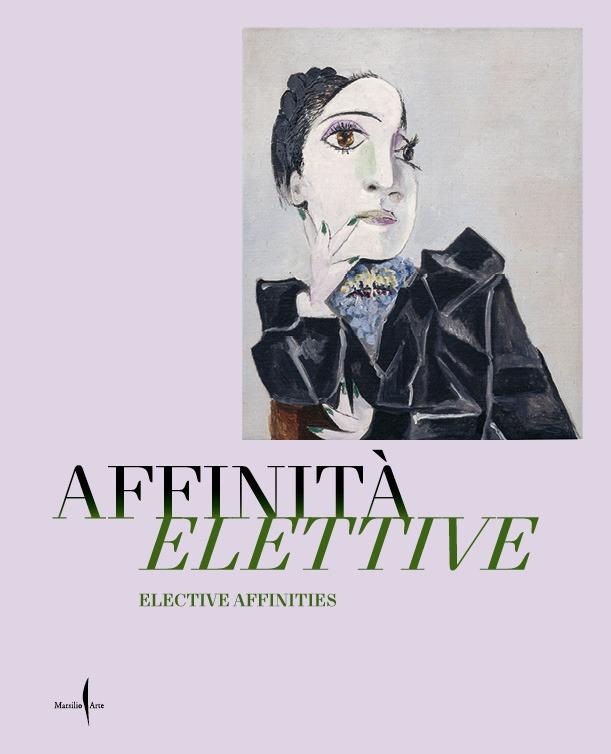

The discovery of the precariousness in which the artist lived and the obstacles he had to overcome during his life in France are the plot not just of Annie Cohen-Solal’s book, Picasso. Una vita da straniero [Picasso. A life as a foreigner] (Marsilio, 2024), but also of the highly original exhibition inspired by it, again curated by Annie Cohen-Solal together with Cécile Debray, and staged from 20 September 2024 to 2 February 2025 at the Palazzo Reale in Milan. Entitled Picasso lo straniero [Picasso the foreigner], the exhibition is sponsored by the Municipality of Milan ‒ Culture, produced by Palazzo Reale with Marsilio Arte and created thanks to the collaboration of the Musée National Picasso in Paris, the Palais de la Porte Dorée and the Musée National de l’Histoire de l’Immigration.

Picasso lo straniero presents around eighty works by the artist, as well as documents, photographs, letters and videos from the Picasso Museum in Paris and the Musée National de l’Histoire de l’Immigration in Paris. An aesthetic and historical journey that invites us to reflect on the issues of immigration and reception, having as its linchpin the figure and work of Pablo Picasso who, despite France having become his home and his fame having brought prestige to the nation, would never obtain French citizenship. Belatedly (1958), they did in fact offer it to him. But by that point he was the one who didn’t want it anymore.

Marco Carminati